How did Finland and Greece end up in the same place on the Rainbow Map?

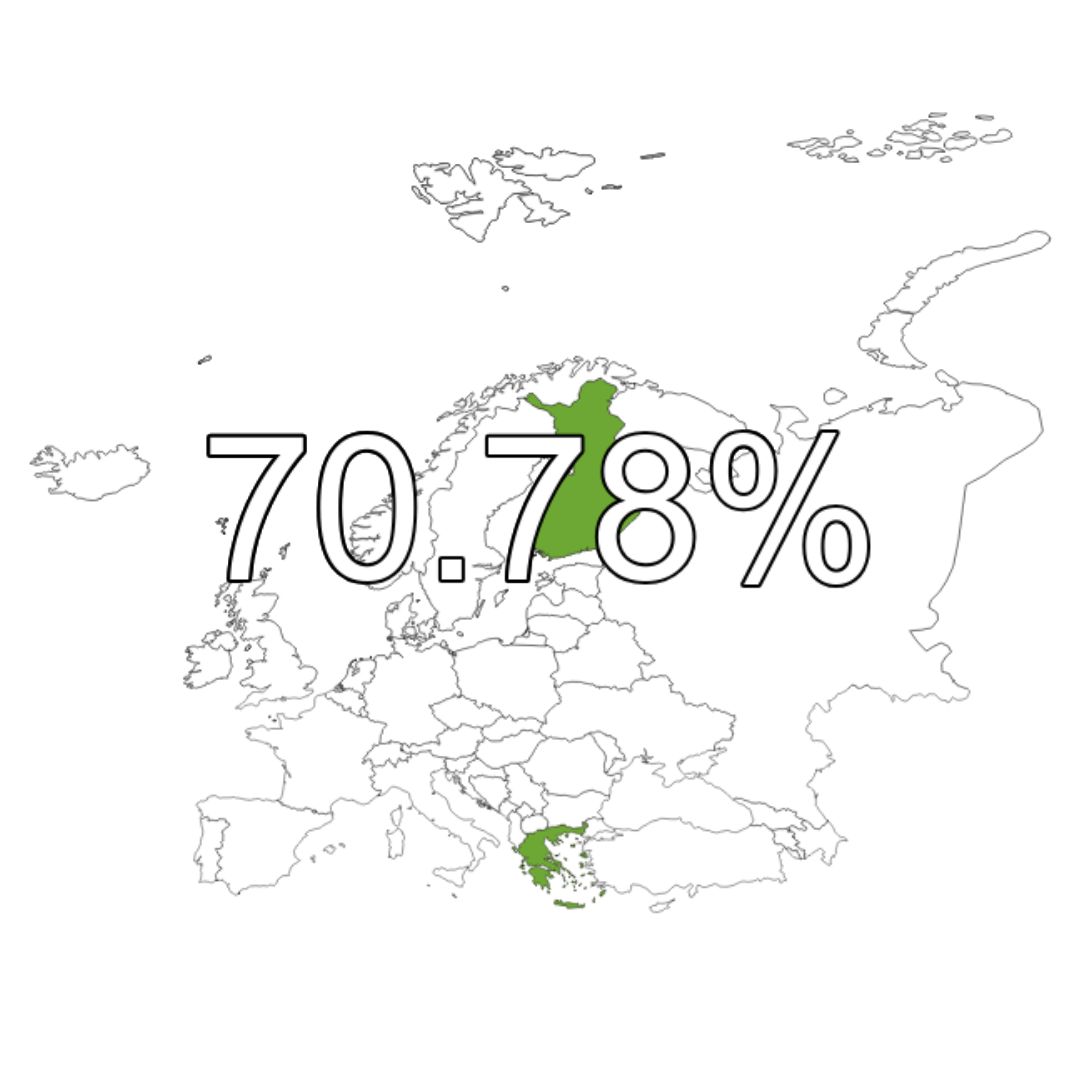

In 2024, Greece and Finland have found themselves sharing the same spot—sixth place—on ILGA-Europe’s Rainbow Map, and that tells us a lot about the diverse ways in which LGBTI rights are changing across Europe.

In an unusual turn of events, Greece and Finland have both secured sixth place on the 2024 ILGA-Europe Rainbow Map. While their scores are identical, the details behind their rankings reveal key differences in their legislative approaches.

What changed from last year?

Finland has retained its sixth-place position from last year, reflecting steady progress in certain areas. A significant development was the lifting of blood donation restrictions for men who have sex with men (MSM) in December 2023. Over 1,700 people have applied for LGR based on self-determination under the new legislation that entered into force in April 2023. However, Finland still lacks a comprehensive LGBTI action plan following the expiration of the Government Action Plan for Gender Equality 2020–2023.

Greece has seen a significant rise from 13th to sixth place, driven by substantial legislative reforms. The introduction of marriage equality, joint adoption, and second parent adoption for same-sex couples marked a major advance. This law also extended non-discrimination principles across various sectors, providing a more comprehensive legal protection for LGBTI people. Despite these gains, Greece faces ongoing issues. Public events in 2023 were reportedly not adequately protected by public authorities, and there has been concern over rising hate speech and hate crimes.

Similarities and differences

Despite their shared score of 70.78% on the Rainbow Map, the legislative landscapes of Greece and Finland are marked by both convergence and divergence. Both countries excel in areas such as employment, education, and health protections for sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics. They also have comprehensive hate crime and hate speech laws, and have ensured the protection of LGBTI civil society.

However, differences in their legal frameworks reveal contrasting approaches to LGBTI rights.

- Finland’s constitution explicitly includes protections for sexual orientation and sex characteristics, a provision that’s absent in Greece.

- Conversely, Greece has enacted bans on conversion practices for both sexual orientation and gender identity, which Finland has yet to adopt.

- Greece also bans unnecessary medical interventions on intersex children.

- Greece has also developed equality action plans covering sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics, which Finland now lacks.

- Finland allows trans people to access legal gender recognition based on self-determination, while in Greece trans activists are still fighting for a fair, transparent legal framework for legal gender recognition based on a process of self-determination and free from abusive requirements.

- Finally, Finland allows medically assisted insemination for couples and recognises trans parenthood, while Greece does not.

Although they are joint sixth place on the Rainbow Map, both countries have long way to go to achieve full equality and human rights for LGBTI people. This is why, with the consultation of LGBTI organisations, we prepared a list of recommendations to improve the legal and policy situation of LGBTI people in both countries.

For Finland, we recommend removing the age restriction in the existing legal gender recognition framework, banning conversion practices, and prohibiting medical intervention on intersex minors. For Greece, our recommendations include introducing a legal framework for legal gender recognition based on a process of self-determination, recognising trans parenthood, and strengthening police protection for LGBTI public events.

The shared ranking of Greece and Finland on the 2024 Rainbow Map is a fascinating case study in the diverse approaches to LGBTI rights within Europe. The Rainbow Map not only tracks these advancements but also serves as a vital tool for identifying areas in need of improvement. For those interested in delving deeper, there is a feature to compare countries, explore individual categories, download datasets and graphics, and gain insights into the current state of LGBTI rights across Europe.

LGBTI activism in the new far-right era

Activists in the Balkans, Greece, Italy and Poland talk about the shared challenges across Europe as the far-right continues to gain ground.

As the far-right gains a serious foothold across Europe, LGBTI groups and organisations continue working and living in the reality that is becoming more and more taxing. Inspired by conversations with activists from Intersex Greece, GayNet Italy, Love Does Not Exclude in Poland, and Trans Mreza Balkans, this blog highlights the shared challenges faced by LGBTI organisations amidst the rising tide of far-right politics. If you are working in an LGBTI NGO, you will undoubtedly find yourself familiar with at least some of these issues.

Financial instability and resource constraints

Many LGBTI organisations face financial instability, relying heavily on external funding with little to no governmental support. External funding poses its own set of challenges as it is often project-based with flexible or core funding hardly available. Such dependency forces organisations to juggle multiple projects. This makes them to expand their expertise in the need to secure necessary funds but it turns to be unstainable in a long run.

Hubert Sobecki, Board Member of Love Does Not Exclude in Poland explains: “We are growing too fast with too few people and too many tasks and processes in hand. The lack of sustainable dedicated funding makes it impossible to plan long-term.” At the same time, strategy and long-term planning is what’s needed in the face of well-organised populist far-right tide.

(Too) rapid organisational growth

Activism is growing as a response to anti-democratic developments and the failure of many states to uphold human rights. Such rapid organisational growth, coupled with limited resources, poses significant challenges. As grassroots movements evolve into more structured organisations, they encounter numerous administrative and operational hurdles as well as a mental toll. These include implementing professional systems, managing cybersecurity, and adapting to increased administrative burdens, while at the same time striving to keep the human-centred family-like essence that many LGBTI groups hold as one of their core values.

Hubert Sobecki from Love Does Not Exclude further notes: “You start as a tight group protesting in the streets and gathering in cafés. Then you find yourself with a large budget and funding to manage, and suddenly you are an employer. This brings internal crises and the need for professionalisation, which we struggle to achieve with limited knowledge, time, and financial and human resources.”

Internal communication

Effective communication and coordination within the LGBTI movement are crucial yet often lacking, as many groups and organisations are pushed into reactive and defensive mode by rapidly growing anti-LGBTI attacks and far-right rhetoric. The rush to respond to external threats and media coverage often lead to disjointed efforts and missed opportunities for collaboration. Additionally, generational differences and varying communication preferences within the community can create friction and hinder cohesive action. Džoli Ulićević from Trans Mreza Balkans says: “There is not enough communication amongst ourselves. Different generations have very specific requests about communication – inside and outside the community.”

Educational gaps and capacity building

The educational systems in many countries fail to adequately address LGBTI issues, resulting in a lack of trained professionals and widespread ignorance and misinformation about the community’s needs. This gap extends to higher education, where legal and social studies often neglect or openly restrict LGBTI topics, leaving future professionals ill-prepared to support the community. Nicole Pikramenou from Intersex Greece emphasises, “There is a profound lack of courses on LGBT and intersex issues in the system of higher education in Greece. Professors who supervise legal theses on LGBTI issues often have no training in these areas.”

Strategic vision

The LGBTI movement both requires and longs for a strategic vision and long-term planning to navigate the complex and evolving political landscape. However, many organisations have had to focus on immediate, reactive measures rather than developing sustained, proactive strategies. Building a long-term perspective, enhancing day-to-day operational skills, and fostering collaboration with broader civil society are essential for enduring progress. Rosario Coco from Gaynet in Italy highlighted the need for “a long-term perspective while boosting our skills in day-to-day tools we use” in the face of rising conservative powers – “for example, it is essential now to know how to debate and prepare for a debate.”

Media representation

Adequate balanced media coverage of LGBTI issues has seen a noticeable decline, contributing to the marginalisation of the community. When LGBTI topics are covered, the media often adopts a sensationalist tone, focusing on what they perceive as the most controversial issues like surrogacy and transgender minors. This perpetuates negative stereotypes, as Rosario Coco from Gaynet Italy observes: “Media talks less about us and at the same time, media is less friendly than before.”

Community building and new ways to do activism

The need for psychological support and community building is critical, especially in regions with heightened hostility. Aleksa Milanović from Trans Mreza Balkans notes: “A lot of young people are joining the movement with specific requests about communication and support. We need to mentor them to think strategically and have a vision.”

Additionally, the need for unrestricted funding to support innovative and effective activism is needed. According to Džoli Ulićević: “We must start being very creative and rethink how we organise, maybe sometimes going back to the door-to-door hit-the-street activism because the old-school rigid NGO model is not working anymore; it is not addressing new challenges and is inefficient the reality we live in.”

More resources

The quotes in this blog were taken in the framework of ongoing conversations we have with LGBTI activists about the impact of rising far-rights. This set of conversations happened as a follow-up on the programme ‘Strengthening the European LGBTI movement in the Context of Rising Anti-LGBTI Forces’ that ILGA-Europe ran in 2021-2022. In the aftermath of the programme we created resource cards for The Hub, our free learning centre for the LGBTI movement.

Greece adopts historic bill introducing marriage equality

We welcome and celebrate with local activists the news that the Greek parliament has adopted an historic bill introducing marriage equality, granting marriage and adoption rights to same-sex couples, as well as fully recognising marriages that took place in other countries, and family ties of children who were born abroad to same-sex parents.

ILGA-Europe and NELFA welcome the news from yesterday, 15 February 2024, that the Greek Parliament adopted a bill introducing marriage equality.

This vote reflects the trend in Greek and European societies towards increasing equality for same-sex couples. The new marriage equality law will grant marriage and adoption rights to same-sex couples, as well as fully recognise all marriages and family ties of children who were born abroad to same-sex parents, and comes as a result of clear political leadership from the current Greek government.

The adoption of this law comes at a time when public acceptance of LGBTI people is on the rise in Greece and across Europe. In fact, an EU survey conducted in 2023 shows that public opinion in Greece as regards same-sex marriage is at an all-time high, marking also the largest increase in approval across all of the EU since the last iteration of the survey in 2019.

The law also follows a number of important legislative steps taken by the current Greek government to improve the access of LGBTI people to their rights and dignity, such as becoming the fifth European country to ban intersex genital mutilation (IGM) in July 2023, lifting the ban on men who have sex with men to donate blood in January 2023 and banning so-called ‘conversion practices’ against LGBTI minors and ‘vulnerable’ LGBTI people in May 2023.

Despite this important step towards equality for LGBTI families, the law does not remove all discrimination as:

- The law does not allow for access to in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) for same-sex couples of two women, meaning that the current discriminatory practice of only single women unable to conceive a child being able to access IVF in a Greek clinic, persists. This should also be made possible for same-sex couples made of two women, who also cannot conceive a child otherwise. Of the 19 EU countries which allow access to IVF for single women, the vast majority of them also allow access to IVF for female couples, coming to a total of 15. This reflects trends across the EU to ensure more equitable access to family and reproductive rights.

- Currently in Greece, altruistic surrogacy is available to opposite-sex couples only, creating a discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation i.e. gay men do not have equal access to the ability to have a child and form a family. The new law has not addressed this.

Greece’s adoption of marriage equality is a hugely important step for the recognition of equality of all couples, and a first step in achieving equality for all parents and people who wish to form a family. We encourage the Greek government to look at the remaining gaps in legislation and to propose measures to bring full equality for rainbow families in Greece.

Join statement by:

- ILGA-Europe

- NELFA – Network of European LGBTIQ* Families Associations

How activism led the way forward to protect intersex children in Greece

To mark #IntersexAwarenessWeeks we look into the efforts and experiences of activists in Greece, who worked for many months alongside the national government, resulting in the country becoming just the fifth in the world to ban intersex genital mutilations on children.

July 19 was a historic day as Greece became the fifth country on the planet to ban genital mutilations on intersex children. Intersex minors under the age of 15, living in Greece, are now protected from surgical operations and other invasive treatments aimed to align their sex characteristics to binary male or female categories.

These unnecessary, non-consensual and abusive interventions have already been banned in four EU countries, Germany, Iceland, Malta, Portugal, and in some regions of Spain. Now Greece has joined these countries in the protection of the bodily integrity of intersex people, a human right that the United Nations, the Council of Europe and the European Union have been calling for for a long time.

How did this happen?

The advocacy work of Intersex Greece has been crucial in bringing this forward thinking legislative change about. During our Annual Conference in Sofia, Nikoletta Pikramenou and Eleni Pateraki, from the organisation, shared their journey towards this historical win.

It all began in 2021 when the Greek government formed a National Committee to design the National Strategic Plan on LGBTQI+ Equality. Intersex Greece submitted a report on the situation of intersex rights. Thanks to this work, the National Plan included, for the first time, a separate section with intersex people’s demands.

Over the course of the following year, Intersex Greece became a registered organisation as well as an ILGA-Europe grantee. They relied on OII-Europe for guidance and attended meetings with the government and the Ministry of Health. LGBT organisations in the country gave interviews to the media and built relations with political representatives.

Intersex Greece worked as a team to best represent the intersex community. While their advocacy strategy relied on the power of personal stories, they made sure no individual felt pressured to come out as intersex.

A week before the vote, Irene Simeonidou, Secretary of Intersex Greece and mother of an intersex child, shared her story with the Greek Parliament. “13 years ago, when I was five months pregnant, two obstetricians at the local hospital suggested, very insistently, that we must terminate the healthy and desirable baby I was carrying because it had an extra X on the sex chromosome,” Irene said. Her testimony shook members of the parliament.

Finally, on 19 July, the bill was voted in and became a law.

In the lead-up to this historic moment, the Intersex Greece team encountered obstacles, due to their limited staff and resources, the emotional stress, and the difficulties of keeping a balance between voluntary activism and their personal and professional lives.

“Our struggles don’t end here. We are here, we are real, we are together,” they remind us in relation to the recent bill.

Hate against intersex people in Greece

Supported by ILGA-Europe, Intersex Greece conducted the first study on hate against intersex people in Greece earlier this year. The conclusions show that negative attitudes towards intersex people prevail in the country, and as a result the implementation of the legislation will be extremely challenging. You can learn more about this research in this moving video developed by Intersex Greece.

Shortcomings in intersex people’s rights in the EU

This year at ILGA-Europe we introduced an Intersex Bodily Integrity category in our Rainbow Map, expanding our assessment of this legislative area from 1 criterion to 4. This is because the introduction of bans in an increasing number of states has helped to clarify the key components in those bans; the new criteria lay out not only the demand that a ban be in place, but also what components the ban should include to meet a minimum standard of human rights protection and effectiveness.

In these countries and territories that receive points on the Rainbow Map, medical practitioners or other professionals are prohibited by law from conducting any kind of surgical or medical intervention on an intersex minor when the intervention has no medical necessity and can be avoided or postponed until the person can provide informed consent. However, in all cases, these bans have serious shortcomings, including that they include exceptions for certain conditions and do not provide universal protection.

The ban in IGM in Greece, is unique, in that in addition to banning surgical interventions, it also bans hormonal interventions that target intersex children – a key demand of intersex human rights organisations.

The work of Intersex Greece and other LGBTI activists in Greece is cut out now to have this legislation fully implemented. And the work of LGBTI activists across the European region is to push governments and policy makers to introduce and shore-up existing legislation to fully respect and protect the human rights of intersex people.

Intersex people exist in every country in the world. These Intersex Awareness Weeks, we reiterate that full autonomy over their own bodies from birth onwards is an inalienable human right for intersex people, and that like every individual, they deserve to live freely, safely and equally in our societies.

Electra Leda Koutra and Anastasia Katzaki v. Greece

Detention and mistreatment of transgender sex workers and their lawyer.

(Application no. 459/16), 13 July 2017

Find Court’s communication here.

- According to the applicants, from May to June 2013, transgender persons were stopped by police officers on streets or taken out from inside of their cars and subsequently brought to a police station in Greece. The first applicant, a lawyer and human rights activist went to the police station – in order to represent a transgender woman – where she was mistreated by the police and placed in a cell for about 20 minutes. The applicants’ complaints against the policemen in charge were discontinued by the Greece authorities.

- ILGA-Europe together with TGEU, Greek Transgender Support Association and International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe addressed the following:

- As the facts of the case were representative of wider patterns of state persecution of (trans) sex workers in Greece and beyond, which typically included assault and arbitrary arrests the submission provided available evidence of this within the broader context. Detailed studies on the situation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia show that sex workers are confronted with high levels of violence from the part of state and non-state actors. Physical and sexual violence by the police reportedly occurs in the course or under the threat of arrest and detention. ‘Facially-neutral’ regulations are often misused to persecute trans sex workers. Studies suggest that trans sex workers in Eastern Europe and Central Asia face higher levels of violence by police than their cisgender peers. Hate crime targeting trans people remains mostly unreported. Even when complaints are duly lodged, police often refuse to register or investigate the allegations in question, effectively blocking the victims’ access to justice and safety.

- Trans people in Greece experience severe isolation, discrimination, prejudice and exclusion on the basis of their gender identity, particularly in relation to accessing and holding employment. Robust and accessible gender recognition procedures are still lacking, leaving many trans people without documents and educational certificates that match their gender identity and thus hindering their access to the regular job market. In order to make ends meet, many trans women turn to sex work, suffering additional stigma as a result. Trans sex workers often face systematic persecution, in the form of police crackdowns targeting marginalized groups.

- Regional and global standards underpin the States’ positive obligation to protect trans sex workers from violence. This includes conducting effective investigation of transphobic crime, particularly when perpetrated by law-enforcement agents and taking into account a bias motive related to gender identity at the sentencing stage. Furthermore, gender identity is a prohibited ground of discrimination under regional and international law. The ECtHR has already found a procedural violation of Article 14 in conjunction with Article 3, based on the authorities’ failure to undertake crucial investigatory steps, including an intersectional analysis, by taking into account the applicant’s “special vulnerability“(B.S. v. Spain, no. 47159/08, 24 July 2012). National and other regional courts have followed the same approach.

Vallianatos & Mylonas v. Greece, C.S. & Others v. Greece

Civil unions

(Applications Nos. 29381/09 & 32684/09), 20 June 2011

Find Court’s judgement here. (Violation of Article 14)

- The applicants alleged that the fact that the civil unions were designed only for couples composed of different-sex adults infringed their right to respect for their private and family life and amounted to unjustified discrimination between different-sex and same-sex couples.

- ILGA-Europe, together with the International Commission of Jurists, the International Federation for Human Rights and the AIRE Centre submitted the following:

- According to the case-law of the ECtHR and national constitutional courts, a strong justification is required when the ground for a distinction is sex or sexual orientation. A growing number of national courts, both in Europe and elsewhere, also required that unmarried different-sex and same-sex couples be treated in the same way and a large number of Council of Europe member States have enacted legislation recognising same-sex relationships.

- The case of Greece was unique, as it was the only European country to have introduced civil unions while excluding same-sex couples from their scope of application.

- The European Court of Human Rights delivered its judgement on 7 November 2013.

- The Court referred to the interveners’ analysis of its own case-law and of national constitutional courts (para 69). The Court considered that the Government had not offered convincing and weighty reasons capable of justifying the exclusion of same-sex couples from civil unions. Accordingly, it found a violation of Article 14 of the Convention taken in conjunction with Article 8.