Solidarity in action: How racialised LGBTI activists are leading the way

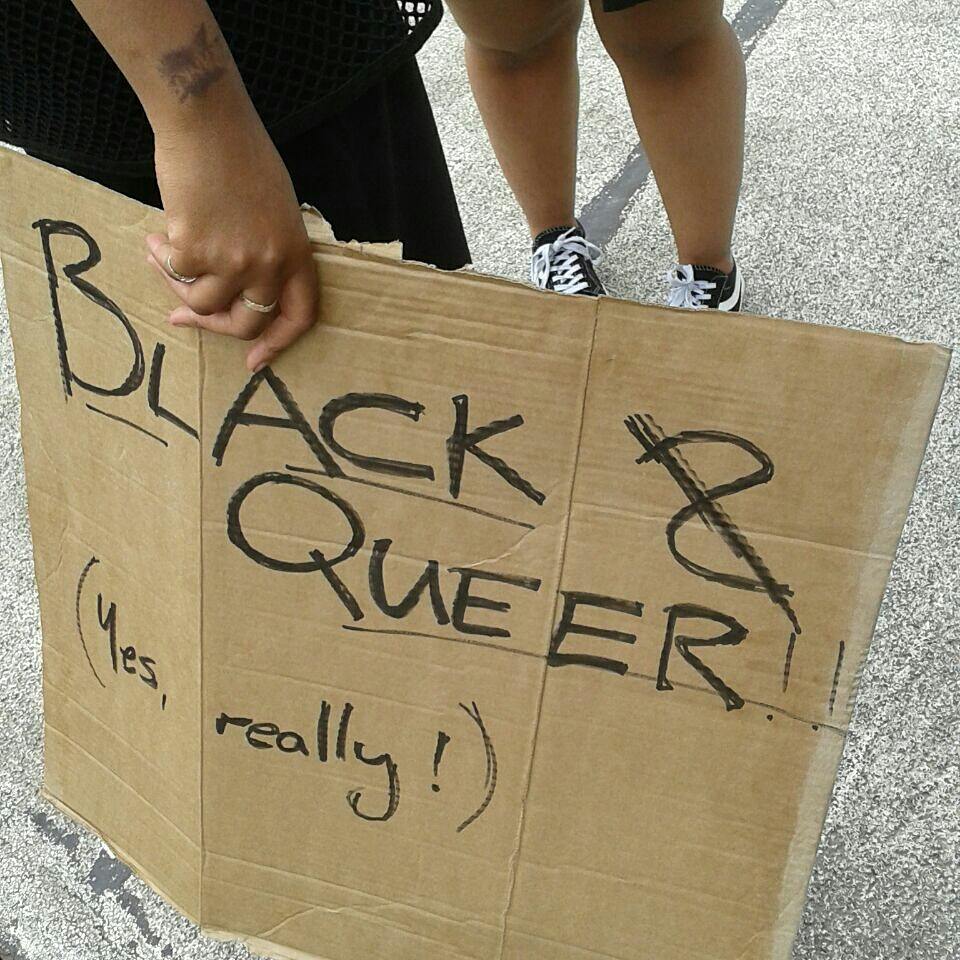

Across Europe, racialised LGBTI activists are redefining solidarity, not as a token gesture, but as a lifeline, a political act, and a practice of care. From fighting deportations to challenging power structures, their work offers a vision for a more just and transformative LGBTI movement.

“Solidarity is a technology of tenderness. It’s love. It’s protection. It’s grace. First to ourselves. Because we, as human beings, we always share what we are filled with.” (Faris Cuchi Gezahegn, Afro Rainbow Austria and House of Guramayle)

“To be radical, [solidarity as politics of affinity] has to be structural. That means dismantling colonisation, racism, LGBTI-phobia. It’s about redistributing discourse, resources, power.”(Pancho Godoy Vega, Colectivo Migrantes Transgresorxs)

With this new blog series, we’re sharing insights from the work of LGBTI organisations tackling injustice, racism, and the unique challenges faced by racialised LGBTI communities in Europe. We hope their stories and practices will inspire and resonate. We believe that solutions and approaches that include a few will pave the way and point to the solutions for many. You can read the previous blog in the series here.

For this blog, we’re shifting our focus to solidarity. What does it mean to racialised LGBTI communities? How is it understood, lived, and practised? And what would it mean for the broader LGBTI movement to engage in solidarity in a truly radical and transformative way?

To explore this, we spoke with three queer racialised groups: Queerstion Media (Sweden), Afro Rainbow Austria, and Migrantes Transgresorxs (Spain). Their stories are both deeply personal yet undeniably political.

Solidarity as a Lifeline

“I am a product of solidarity,” says Purity K Tumukwasibwe, Executive Director of Queerstion Media. “I became an activist by default. I was advocating for myself because otherwise my rights were just completely taken away from me.” From surviving police violence in Uganda and Kenya to being supported by a network of queer activists and allies in Europe, Purity’s journey is an example of how solidarity can be a lifeline, a practice that literally saves lives.

She shared a recent story of advocating for a fellow trans refugee in Sweden who was facing deportation to Uganda. “Everybody said that if the migration services decided on that, then it was over. But we said, ‘Let’s try’. I was so impressed by how everybody came on board.” Through a petition, media outreach, and institutional pressure, united in solidarity, they changed the outcome. The woman was granted residence in Sweden and permitted to stay. “When I see these members we support, who we come together for, I feel like I have contributed to a better world,” says Purity.

A Technology of Tenderness

For Faris Cuchi Gezahegn, member of Afro Rainbow Austria and co-founder of House of Guramayle, solidarity is both a political act and a spiritual practice. “To exist in this world as the person that I am, I am the manifestation of solidarity,” they say. Faris speaks of the collective effort that ensured their survival as a queer Ethiopian activist forced to flee, and how those acts of support were never transactional, but rooted in mutual care.

For Faris, solidarity isn’t about identity politics or rigid definitions. “It’s a technology of tenderness,” they explain. “It’s love. It’s protection. It’s grace. First to ourselves. Because we, as human beings. We always share what we are filled with.”

Yet, Faris also sees an urgent need for transformation within the LGBTI movement itself. “We harm one another. We are often encircled by the violence projected onto us, and we replicate it – in our accountability practices, in our scarcity mindsets, in how we treat one another.” Their call is for radical healing: to resist punitive impulses and lead with softness, honesty, and vulnerability.

Beyond Solidarity Towards Structural Change

The collective Migrantes Transgresorxs challenge the word ‘solidarity’. “We prefer to talk about the politics of affinity,” says Alex Aguirre Sánchez. “Solidarity carries a violent historical weight. It comes from religious charity, and religion has been violent for us.”

Instead, they emphasise ancestral bonds and community-to-community alliances. “We stay together, and together we are stronger,” says Kimy/Leticia Rojas. “It’s about sharing food, music, lived experience, and ancestral knowledge.”

Pancho Godoy Vega adds: “To be radical, it has to be structural. That means dismantling colonisation, racism, LGBTI-phobia. It’s about redistributing discourse, resources, power.” The group, formed in Madrid in 2009, has always intertwined the personal and political – fighting for trans migrants, critiquing whiteness in LGBTI spaces, building alliances from the bottom up.

All the activists featured in today’s blog share this in common: they call for a solidarity that is not superficial or symbolic, but material, embodied and rooted in justice. It means funding grassroots work. Sharing platforms. Redistributing power. Above all, it means healing.

As Purity puts it: “There is always going to be two sides of that coin, those with resources, and those at the margins shouting that we are struggling. Bridging that gap means planning together. It means putting grassroots like ours on the agenda.”

Skills Boost: Useful communications strategies for LGBTI activists

We covered:

- What is a communications strategy? (and how is it different from ‘strategic communications’?) What is the point of it?

- What is the minimum that any communications strategy should cover, and what is the menu of options if one wants to be a bit more ambitious?

- Hearing from two LGBTI organisations who have gone through a communications strategy process recently – and what they learned from their experience. Check the experience of the Newcomers project (Sweden) and Transakcija (Slovenia)!

You might want to check other comms resources by ILGA Europe:

- 9 Steps to a Good Communications Plan (Hub card):https://hub.ilga-europe.org/communications/9-steps-to-a-good-communications-plan/ know where to start? Reach out to us, we might be able to help! Contact svetlana@ilga-europe.org.

- Useful communications for LGBTI-activists: take it to a new level (SkillsBoost recording): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YX3U-4KG5xY

- to be published Communications Strategies for Small Organisations (a Hub card): https://hub.ilga-europe.org/communications/communications-strategies-for-small-organisations/

Do you struggle with some specific communications challenge, and do not know where to start? Reach out to us, we might be able to help! Contact svetlana@ilga-europe.org

Greater legal protection for trans people on the way in Sweden

Hours before International Day against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia, the Swedish parliament declared their support for greater legal protection for trans people.

There are two distinct legal processes going on, in relation to hate crime and hate speech laws respectively.

In relation to hate crimes, on 16 May Swedish MPs voted in favour of adding the ground of ‘transgender identity and expression’ to the existing list of protected grounds in the current 2010 legislation. (The new list of protected ground will read as follows: race, skin colour, national or ethnic background, faith, sexual orientation and transgender identity or expression.) This change is due to come into effect on 1 July 2018.

On the same day, MPs also took the first step required to add the transgender identity and expression ground to hate speech laws. This will require constitutional change so the timeline is slightly different to the hate crime amendments; the parliament will need to vote for a second time on this issue following general elections scheduled for autumn 2018. This proposed change would then enter into force on 1 January 2019.

According to RFSL, if successfully passed, this would be the first time that trans people are recognised in the Swedish constitutions. However, both RFSL and RFSL Ungdom expressed concerns around the phrasing of the ground itself; ‘gender identity and expression’ was the preferred option.

ILGA-Europe are pleased to see movement on hate crime and hate speech laws in Sweden so soon after the publication of our latest Rainbow Europe Map earlier this week.

- UPDATE: On 14 November, the Swedish parliament took the second of two necessary decisions to include trans people in the Freedom of Speech act’s regulation on hate speech. The first decision came in May of this year. The legislative change comes into effect on 1 January 2019. In two steps, trans people have now been given increased protection in Swedish legislation. Since 1 July, trans people are protected within the hate crime legislation. At the same time “transgender identity and expression” was added as a protected ground for unlawful discrimination and insult.

wedish Parliament to pay compensation for forced sterilisation of trans people

Yesterday, the Swedish Parliament took the historic decision that trans people who were forcibly sterilised (between 1972 and 2013) should be paid compensation. This is a worldwide first, and it is the result of a long fight from trans activists.

Their initial fight was against the requirement that trans people must be sterilised in order to get their gender legally recognised.

This major human rights violation stopped in Sweden in 2013 – but the work of activists did not end there. 160 individuals who had been forcibly sterilised submitted a claim for compensation and in April 2016, the Swedish Government announced such a measure would be put forward.

It is estimated that 600-700 people will be eligible for this compensation of 22,500 euros.

As Emelie Mire Åsell, the trans and intersex spokesperson of RFSL says, “money can’t undo the harm of unwillingly losing your reproductive abilities, but the monetary compensation is an important step for the state to make amends to all those subjected to this treatment”. Now, RFSL hopes that the government will also officially apologise to the whole trans community for the harm done.

ILGA-Europe calls on the 27 European governments that have not yet outlawed the forced sterilisation of trans people to urgently put an end to this extremely harmful practice.

- RFSL’s statement on the Swedish Parliament’s decision can be found here.

- Sweden currently sits at 12th in the Rainbow Europe ranking on law and policy.

A.T. v. Sweden

Asylum

(Application no. 78701/14), 19 May 2015

Find Court’s decision here. (struck out of the list of cases)

- The applicant complains under Articles 2 and 3 of the Convention that his expulsion from Sweden to Iran would expose him to a real risk of being sentenced to death or subjected to torture or ill-treatment because of his sexual orientation.

- ILGA-Europe together with the AIRE Centre, Amnesty International, the ICJ and the UK Lesbian and Gay Immigration Group submitted the following:

- Requiring coerced, including self-enforced, suppression of a fundamental aspect of one’s identity is not compatible with the Convention.

- The criminalization of consensual same-sex sexual conduct gives rise to a real risk of Article 3 prohibited treatment, thus triggering non-refoulement obligations.

M.E. v. Sweden

Asylum

(Application no. 71398/12)

Find the Chamber 2014 judgment here and the final Grand Chamber 2015 judgement here. (Struck out of the list of cases as the applicant was granted a permanent residence permit in Sweden)

- The applicant, a married gay man, alleged that his expulsion to Libya in order for him to apply for family reunion from there would entail a violation of Article 3 of the Convention..

- ILGA-Europe, together with FIDH (Fédération Internationale des Ligues des Droits de l’Homme) and ICJ (International Commission of Jurists) submitted the following:

- There is a consensus in European and other democratic societies in support of gay and lesbian asylum and of greater recognition of, and protection for, the right of gay and lesbian individuals to ‘live freely and openly’. According to national, European and international human rights law standards, an LGBTI person cannot be expected to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity in their country of origin to reduce the risk of ill-treatment. Concealment may also result in significant psychological and other harm.

- The interveners provided background country evidence demonstrating that a gay man open about his same-sex marriage in Libya faced substantial grounds for fearing a real risk of arrest, abduction and physical assault by state sanctioned militia. Gay men could not live freely and openly in Libya, without the risk of treatment contrary to Article 3. Even where the exposure to a risk of treatment contrary to Article 3 is expected to be temporary, the period of expulsion is immaterial, because the right to be protected against ill-treatment is absolute.

- Latest update on the situation: the threat of a violation was removed by the Migration Board’s decision (2014) of repealing the expulsion and granting the applicant permanent residence in Sweden.